For an hour on the morning of June 8, dozens of the world’s most-visited websites went offline. Among those affected were Amazon, Reddit, PayPal and Spotify, as well as the Guardian, the New York Times and the UK government website, gov.uk. Together, these websites handle hundreds of millions of users.

The issue was quickly traced to Fastly, a cloud computing company which offers a content delivery network to the affected websites. Designed to alleviate performance bottlenecks, a content delivery network is essentially a system of computers or servers that hold copies of data across various points of a network. When it fails, the websites it supports cannot retrieve their data and are forced offline.

On June 8, we experienced a global service interruption. Here is what happened — and what happens next.https://t.co/gffDur5Moh

— Fastly (@fastly) June 9, 2021

The outage to Fastly’s content delivery network appears to have been caused by an internal software bug that was triggered by one of their customers. Yet even though it was resolved within an hour, it’s estimated to have cost Fastly’s global clientele hundreds of millions of dollars.

This case illustrates the fragility of an internet that’s being routed through fewer and fewer channels. When one of those major channels fails, in what is called a “single point of failure”, the results are dramatic, disruptive and incredibly costly.

This hasn’t been lost on cybercriminals, who know that one targeted hack can bring down or breach a number of organisations simultaneously. It’s urgent we address this significant vulnerability if we’re to avoid another global internet meltdown – but this time caused by criminals, not code.

Warning signs

Given that it came hot on the heels of the ransomware attack on the Colonial oil pipeline in the US, experts initially speculated that Fastly’s outage could have been caused by a cyberattack.

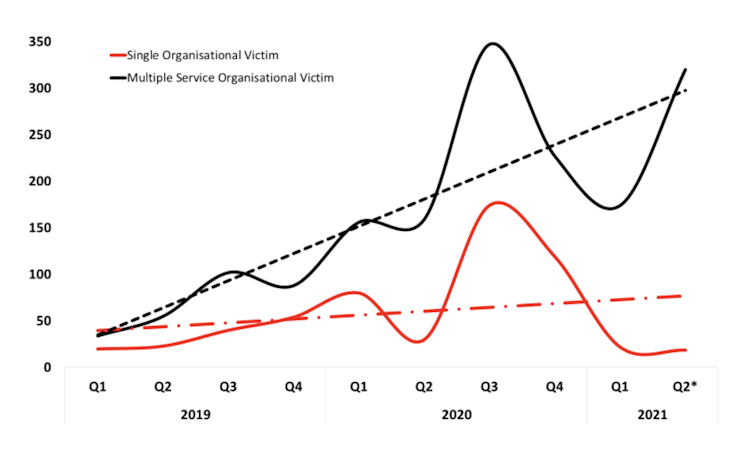

It’s easy to see why. Drawing upon an analysis of over 4,000 ransomware attacks, my research has revealed a massive acceleration in major cyberattacks that target organisations, conducted by ransomware gangs looking to extort cash from businesses they manage to hack.

These attacks are taking advantage of vulnerabilities caused by remote working arrangements. But there’s also been a noticeable shift in attacks upon organisations like Fastly, which provide core services to other organisations and their own clientele.

David S. Wall, Author provided

This trend is unlikely to stop. Ransomware has become a sophisticated billion-dollar business, and attackers are supported by an increasingly professional ecosystem that’s incentivised by the high yield generated by such attacks. A 2020 Verizon report found 86% of hacks are financially motivated, while less than 10% are motivated by espionage.

Two high-profile hacks that targeted organisations with access to thousands of other organisations have recently shown just how fragile centralised internet systems can be. The SolarWinds and Microsoft Exchange Server hacks, which took place in early 2020 and early 2021 respectively, breached tens of thousands of companies. Both have been attributed to state-backed hackers, rather than ransomware gangs.

But cybercriminals have deliberately targeted multiple service providers and critical supply chains too in order to upscale the impact, and therefore the potential payout, of their hacks. Blackbaud, Accellion and other key online service providers have been victim to such attacks.

Centralisation of the internet

All these particularly disruptive hacks are partially the result of the drive towards centralisation of online services, which may be efficient for businesses, but is counter to the founding principles of the internet.

The initial appeal of the internet was that it was a distributed network designed to resist attacks and censorship. When released for public use in the early 1990s, the internet became popular for commerce as well as being regarded as a beacon of free speech. But market logic, rather than free speech, has driven developments since the early days.

Today, cloud computing firms and multiple service providers manage large chunks of internet traffic, causing single points of failure where internet flows can be accidentally or deliberately disrupted. Even something as simple as a typo can cause significant disruption, as was the case in 2017 when several of Amazon’s servers – which power large swathes of the internet – went temporarily offline due to an inputting error.

We should take our hats off to Fastly for quickly rectifying the June 8 outage. But this case has revealed the dangers of consolidating key internet infrastructure, resulting in the emergence of costly single points of failure. It’s another stern wake-up call for law enforcement and the cybersecurity community, giving renewed emphasis to the mission of the US and European ransomware taskforces.

Avoiding internet meltdowns

But are taskforces enough to address this problem? What this event has really shown is how firms like Fastly are in effect privately-owned public spaces, which not only blur the lines between business and national infrastructure, but have, in effect, become “too big to fail”.

All this suggests that the solution to this dilemma must be found beyond multi-sector taskforces, requiring full-blown political debate over what we want the internet to look like in the latter three-quarters of the 21st century. If we fail to make that decision, then others will for us.![]()

Written by David S. Wall, Professor of Criminology, University of Leeds and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.