UAE Mars mission: extraordinary feat shows how space exploration can benefit small nations

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) successfully launched its Mars mission dubbed “Al Amal”, or “Hope”, from the Tanegashima Space Centre in southern Japan on July 20. This is the first space mission by the UAE, and the first Arab mission to Mars – making the world’s first launch countdown in Arabic a moment for the history books.

The mission’s journey to its launch date has arguably been at least as remarkable as the launch itself. With no previous domestic space exploration experience, planetary science capacity or suitable infrastructure, the nation managed to put together a delivery team of 100% local, Emirati staff with an average age of under 35. And setting a deadline of six years rather than ten, as most comparable missions do, it pulled the launch off on time and within budget – now proudly joining the small cadre of nations who have launched a mission to reach Mars.

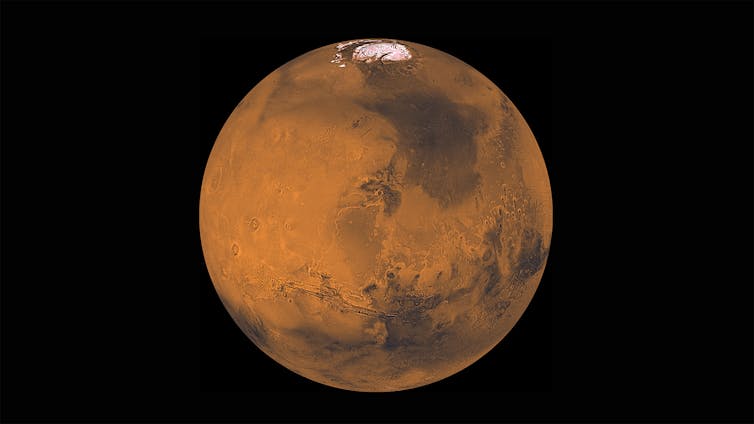

But given these odds, and the fact that Mars missions are notorious for their high failure rates (about 30% since the early 2000s), why did the UAE aim for the red planet in the first place? Space programmes have historically been used as catalysts for geopolitical influence. What’s more, we often think of them as costly endeavours of scientific curiosity, with few immediate and tangible benefits here on planet Earth. Does this reflect the UAE journey?

Space missions typically depart trying to answer scientific questions, before they ask how their value can extend to the society behind it. The Hope mission, however, has inverted this traditional logic. Instead, its conception arose from a quest to fundamentally redirect a nation’s trajectory.

The UAE’s mission has been timed to coincide Hope’s arrival into Martian orbit with the nation’s 50th anniversary as an independent country. Through its design and execution, the mission aims to diversify UAE’s economy from traditional activity, including oil and finance. Instead, it wants to inspire a young Arab generation towards scientific and entrepreneurial careers – and away from other, less societally beneficial pathways.

NASA/JPL/USGS

Hope will also study the Martian atmosphere and gather data to generate the first truly holistic model of the planet’s weather system. The analysis and insights generated will help us better understand the atmospheric composition and ongoing climate change of our neighbour planet.

Lessons for aspiring nations

What could other nations learn from this distinctive approach to space exploration? Can a space mission really transform a national economy? These are the questions at the heart of an external review of the Emirates Mars mission undertaken by a group of researchers at the Department for Science, Technology, Engineering and Public Policy at University College London.

Over the course of five months, we undertook a comprehensive evaluation of the impact and value generated by the mission less than five years after its inception. What we found was that there’s already evidence that the mission is having the intended impact. The country has massively boosted its science capacity with over 50 peer-reviewed contributions to international space science research. The forthcoming open sharing of Hope’s atmospheric data measurements is likely to amplify this contribution.

The nation has also generated significant additional value in logistics by creating new manufacturing capacities and know-how. There are already multiple businesses outside the realm of the space industry that have benefited from knowledge transfer. These are all typical impacts of a space mission.

But while that is where most studies of the value of space missions stop looking for impact, for the UAE this would miss a huge part of the picture. Ultimately, its Mars mission has generated transformative value in building capacity for a fundamentally different future national economy – one with a much stronger role for science and innovation.

Through a broad portfolio of programmes and initiatives, in just a few years the Hope mission has boosted the number of students enrolling in science degrees and helped create new graduate science degree pathways. It has also opened up new sources of funding for research and made science an attractive career.

One of the lessons is therefore that when embedded within a long-term, national strategic vision, space exploration can in the short term generate major benefits close to home. While space may appear to primarily be about missions for science, when designed in this way, they can be missions for national development.

Hope will reach Martian orbit in February 2021. Only then will its scientific mission truly take off. But its message of Hope has already been broadcast.![]()

Written by Ine Steenmans, Lecturer in Futures, Analysis and Policy, UCL and Neil Morisetti, Vice Dean (Public Policy) Faculty of Engineering Sciences, UCL and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.