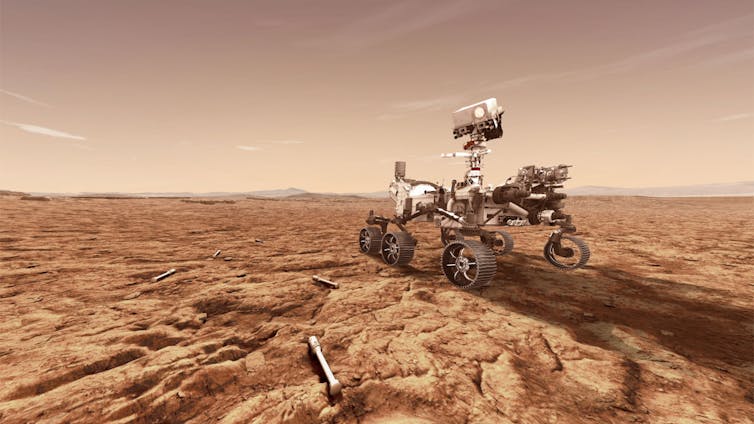

We’ll soon be able to properly start asking the question: “Are we alone in the universe?” Nasa’s next major mission, the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover, will land on the surface on February 18. Following a complex landing procedure, it will get started on one of its main goals – searching for life on Mars.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

The rover has two ways of gathering samples. It can either analyse them with its on-board laboratory or it can save them for return to Earth by future missions. But what exactly is it looking for, and what would it need to find to convince us that there is indeed past or present life?

If the landing is successful, this will be the first mission in decades to actively search for direct evidence of life on Mars. This life – if it exists – will most likely take the form of extinct microbes.

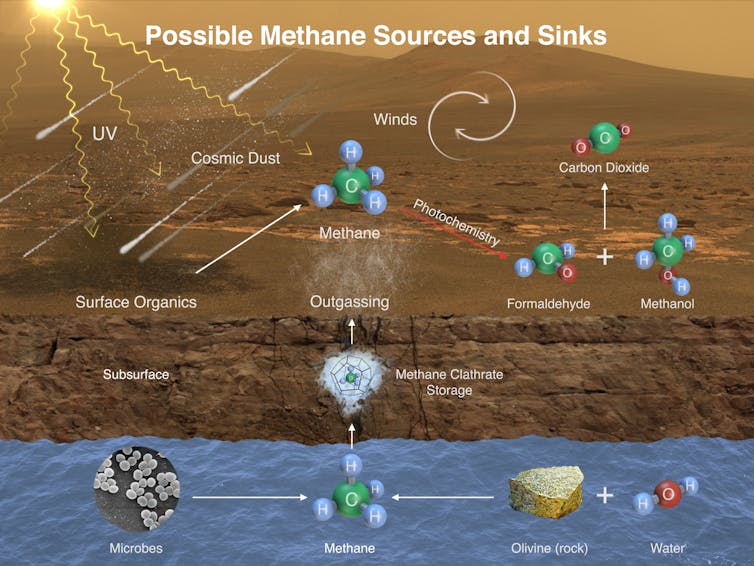

We have recently found some tantalising hints at the possibility for current life in the form of methane gas in the atmosphere. On Earth, a large percentage of methane in the atmosphere is produced by biological processes. This means that methane could be considered a biological signature. But it can also be readily produced by geological processes, so it is not proof of life.

Nasa

There are many molecules that are only made by terrestrial biology, such as isoprene or DNA. So finding something like those would allow us to move toward the conclusion that life exists or existed on Mars. If Perseverance does find such molecules, we will have the harder job of proving it was native to Mars and not a microbial hitchhiker from Earth. To help us work that out, the rover will first run “control experiments” with no sample. If the molecules are there in these experiments, they are likely to be terrestrial contamination on the rover itself.

Sophisticated instruments

That said, if we find molecules that are not readily produced by standard chemical reactions on Mars, we might be onto something biologically alien. One of the instruments that will be used to search for biosignatures on Mars is SHERLOC (Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals). It will use an ultraviolet laser light to probe samples from a safe distance of about 5cm. This way it reduces the chance of contaminating the samples while measuring the reflected light for evidence of biological molecules.

This works because each molecule type reflects the light in a unique way, allowing us to determine with a high degree of certainty that we have found something like amino acids (which build proteins) or lipids (which build cell walls). These molecules are known to persist in the environment after other biological molecules like DNA have been broken down and are no longer detectable.

Perseverance will also carry the SuperCam instrument, which can shoot a laser to a distance of around seven metres. It can analyse the resulting dust cloud for evidence of rock types that could preserve clues to past life. This helps narrow down locations that might be best to investigate more fully without having to take the time to drive to them.

Nasa/JPL-Caltech

Rock samples from a depth of around 5cm will also be collected and stored in sealed containers for a future mission to collect. The analysis we can conduct on Earth is many times more precise and detailed than the instruments we can send to Mars. Plus we can do multiple kinds of analysis in multiple labs around the world, allowing for better overall results. For example, if evidence for extinct life is suspected to be preserved in a sample, we could use electron microscopy (which uses electrons rather than light to probe a sample) to try and see if it contains fossilised microbial cells.

All of this depends on our very narrow understanding of what life is. We only know about one kind of life – the terrestrial kind. Our experiments are searching for life within our current knowledge. It is always possible that life beyond our current understanding exists, perhaps silicon-based rather than carbon-based. Perseverance isn’t likely to detect such life even if it’s thriving on Mars.

Unless something gets up and moves in front of the camera, obtaining conclusive evidence likely be a long process, especially while we wait to analyse those cached samples. If we find even a hint of evidence for life, the next steps will be to detect it with multiple analytical techniques, show that it isn’t contamination from Earth and work out whether the evidence make sense in the context of the environment and data from the other instruments.

Any evidence for life will have to go through the rigorous scientific process of testing, re-testing and peer review. What’s more, Perseverance is only conducting analysis in one crater on Mars.

But other missions in the search for life, including the European Space Agency’s Rosalind Franklin rover, aren’t far behind. Excitingly, Rosalind Franklin will be the first to drill up to 2m under the harsh, freezing Martian surface. If there is any current life on Mars, we might be more likely to find it deeper below the surface, which is constantly bombarded with harmful radiation.

Written by Samantha Rolfe, Lecturer in Astrobiology and Principal Technical Officer at Bayfordbury Observatory, University of Hertfordshire and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.