“Women, your country needs you,” Millicent Fawcett, the campaigner for women’s suffrage, proclaimed when war was declared in August 1914.

One enthusiastic respondent to the call was Helena Gleichen, a rich aristocrat and a cousin of George V who had dined with Queen Victoria, danced at debutante balls and spent much of her life riding or painting animals. But when the war started, she renounced her Germanic family titles and committed herself to war work. More than 100 years after the armistice was signed, Gleichen has become a forgotten hero of the World War I – despite her brave contributions having saved thousand of lives on the Italian Front.

Although the British Army scornfully refused offers from women willing to travel overseas, that failed to stop many brave volunteers from getting involved. Although now forgotten, Gleichen was Britain’s war-time Marie Curie – the Polish scientist who invented mobile X-ray units that she took to the French front. While Curie was saving French lives, this English landscape artist was rescuing Italian soldiers.

© IWM

Medical radiography was still in its infancy. The German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had discovered X-rays in 1895, and the following year created the first X-ray photograph, memorably revealing the bones of his wife’s hand. Two decades later, suitable machines were available in major hospitals, but they were located too far away to help soldiers injured on the battle field.

Curie won two Nobel Prizes for her pioneering research into radioactivity, but during the war she abandoned her laboratory to support her adopted country. Her Curie cars brought radiography equipment – including miniature dark rooms for developing prints – right to the scene of battle, so that soldiers could be examined and treated immediately.

In 1915, Gleichen and her friend Nina Hollings converted a French chateau into a military hospital before travelling to Paris and training with X-rays. But the War Office informed them with unassailable illogic that because no women were radiographers it was impossible to employ them. Undeterred, they came back to London and organised their own relief operation.

To get advice, Gleichen contacted the distinguished Scottish pioneer of medical radiography, James Mackenzie Davidson. She raised enough money from her wealthy family to buy one of the new portable machines he was developing, as well as a specially adapted Austin car to drive it in.

Eve Curie/Wikimedia Commons

Gleichen and Hollings set off for Italy, where they settled just behind the frontline in a country villa near the border town of Gorizia. Their home became a busy X-ray department, its machinery powered by a cable snaking along the hallway from the car parked outside. Alone in the middle of a battle zone, the pair learnt how to service their electrical equipment and fix their car. On one occasion, Gleichen enterprisingly melted two large altar candles to replace some cracked insulation.

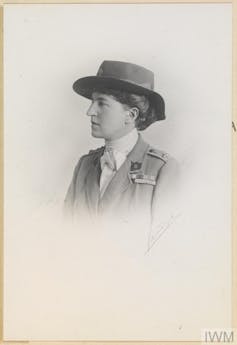

Although photos show two demure women in heavy uniform, hats firmly in place even when working inside, Gleichen recounts adventures as hair-raising as those of any frontline soldier. Often at risk from enemy bullets, they took many thousands of X-rays, eventually damaging their hands and their eyes.

In a letter to Davidson, Gleichen explained that they needed to work quickly. With more and more wounded soldiers arriving daily, many of them already close to death, there was often no time for the luxury of standard procedures. Weighing down their un-anaesthetised patients with sandbags, they explored precisely yet rapidly to locate bullets lodged in a soldier’s body by a rough-and-ready technique of aiming along two perpendicular lines to see where they intersected.

Gleichen was particularly jubilant about managing to pinpoint a bullet deep inside a soldier’s skull. She sent Davidson a small sketch, telling him that she was “cocka hoopy”. Despite this experimental success, she faced up to wartime realities: “Anyway it has been deeply interesting + I expect they will kill him by operating + equally kill him by leaving it. I am sorry as he was such a nice boy in tremendous spirits + health.”

Gleichen was forced to leave rapidly when Gorizia fell in 1916, but after the war she was awarded medals by both Britain and Italy for her distinguished contributions. In her memoir, she wrote: “And after the War? What then? As with many other people, we were incapable of sitting still, or of resuming a normal existence.”

Gleichen was one of the women who were able to experience the freedom and independence which are normally deserved for men. Although she later returned to her apparently contented rural life as an artist, she had – like so many other women – become a different person.

Written by Patricia Fara, Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, University of Cambridge and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.